When COVID-19 cases in the US began to spike in March, Hikma Health, a digital health startup from the Harvard i-lab and winner of the 2019 Harvard Business School (HBS) New Venture Competition, asked how they could best help to stop the spread of COVID-19. Following a hackathon, extensive brainstorming, and research, it became clear that despite its enormous value, COVID-19 policy data at the more granular county level was virtually nonexistent. In response, HBS MBA students teamed up with Hikma Health to crowdsource the first and largest COVID-19 county policy dataset for researchers, as well as a corresponding interactive map for empowering the public to directly interact with raw COVID-19 data. We caught up with project lead, Cray Noah (MD/MBA 2022) and one of the student volunteers, Daniel Ocampo (MBA 2020) to learn more.

Where did the idea for this project originate?

Cray: After the hackathon, the need for this more granular type of policy data intensified as two things became clear: First, COVID-19 behaves very differently from county to county. Second, since vaccines and medications have lengthy lead times, so-called non-pharmacological interventions (NPIs), like shelter-in-place policies and public testing centers, are the most effective and initially only option to limit the spread of coronavirus. To fill this need, MBA students teamed up with Hikma Health on a purely volunteer basis to collect the data.

What is the project’s primary goal?

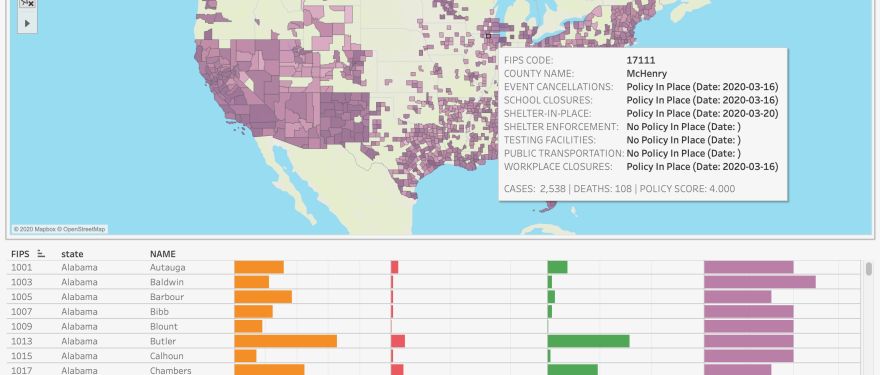

Cray: The ultimate goal has been to fill a gap in COVID-19 data. By creating a higher resolution dataset/map, we’ve enabled policymakers, epidemiologists, and economists to perform more representative and applicable research that will inform local policy decisions to come. More specifically, we recently received COVID-19 research seed funding to “double-code” all 1,320 counties in the dataset (the gold standard of data validation for crowdsourcing in which multiple people research the same outcome and reconcile any response differences). We also recently received inbound interest from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to include the dataset in the official federal COVID-19 reporting system, which we’re very excited about. Once fully double-coded, the ultimate hope is that HHS and many other outlets will endorse and post this valuable county-level dataset/map so it gets into the hands of as many people and research groups as possible.

How did the project grow, and how did the students contribute to that growth?

Cray: It started as a small grassroots project with 10 MBA students and a goal of collecting data on 100 counties. Now, it’s a nationwide 100+ volunteer effort, resulting in a research caliber dataset covering those 1,320 US counties and also 154 Native American communities, and inbound funding offers to continue the project.

Daniel: HBS MBA students across classes 2020-2022 contributed at all stages, but most importantly early on. Most of the initial volunteers like myself built out a prototype/visual to use when pitching the opportunity for further support. From there, the HBS network helped the project really catch fire. We leveraged our connections with research groups, faculty, and other institutions to get valuable feedback from experts and help disseminate the volunteer opportunity to organizations like MBAs Fight COVID-19 and the National Student Response Network, as well as email listservs, and Slack channels.

As word spread through the tight-knit HBS community, we received tremendous and unexpected levels of inbound interest, starting with students across all Harvard University and spreading to student volunteers from over 20 academic institutions across the country. Staying predominantly within graduate student circles helped serve as a quality control—many students applied the same level of rigor to this data collection effort as they did for their academic projects.

What has been the reaction from COVID-19 researchers? How is the data being used?

Cray: Initially, many of the experts we reached out to were optimistic but skeptical that the dataset would be large enough for reliable analysis—this kind of granular data must be crowdsourced, and we were relying purely on volunteers. But once the project surpassed 1,000 counties, interest really picked up. Epidemiologists, economists, and physicians have been impressed by the amount and quality of data we’ve collected and encouraged us to publish our crowdsourcing protocol and strategies, which we’re in the process of doing.

As for the dataset, it is completely free/opensource and is already becoming the preferred policy dataset over more general state-level data. It’s been accessed thousands of times and used by modelers at local governments, hospitals, and universities around the country to inform COVID-19 policy next steps. To name a few current examples, local groups at Mass General and Brigham and Women’s hospitals are coupling our county-level policy dataset with COVID infection and population datasets to analyze which policy interventions work best for specific counties given their immense differences; an economics group at Amherst College is using our dataset to find links between COVID responses and rugged individualism; and Emory University epidemiologists are using the dataset to perform natural experiments quantifying efficacy of the policy interventions used in the U.S., results that can be applied to this pandemic or any future public health crisis.

Other research groups at Harvard, Stanford, and Columbia Universities have notified us they are finding correlations previously unseen with state-level policy analysis by using our dataset, which can be coupled with any number of other data sources to perform unique and more detailed analyses on factors like demographic disparities, political alignment, or population density in relation to local COVID-19 policies.

What’s next for the project?

Cray: To scale this unique resource further we need to secure more funding, which would enable us to expand beyond 1,320 counties, include more policies, keep the dataset dynamically updated, and potentially create a standalone website to serve as a hub for all county-level COVID-19 data and real-time analysis.

If someone is interested in volunteering, where should they go for more information?

Cray: If you would like to contribute to this project in any way, whether it be through funding, data collection, spreading the opportunity, sharing or using the dataset or the interactive map, please email covidpolicies2020@gmail.com. Links to the completely free and opensource dataset and associated interactive map can be found here:

- Dataset: GitHub.com/HikmaHealth/COVID19CountyMap

- Map: HikmaHealth.org/Map

What has this experience been like for both of you?

Cray: Seeing my fellow HBS MBA students rally together on a volunteer basis to contribute in non-flashy ways through data entry and recruitment, especially in such uncertain and stressful times, has been inspiring. And the degree to which it has happened was completely unexpected.

While recruiting and managing volunteers, organizing the data on the back end, and establishing standardized protocols has become a full-time job and shifted my summer plans, it’s been more than worth it. Seeing the commitment of my fellow HBS classmates in bringing the project to the point of having a real research impact has been fantastic. It really demonstrates the character of HBS students and reflects the mission statement of the school to a T.

Daniel: As one of the early volunteers helping get this project off the ground, it’s been rewarding to see so many of my classmates step up and meet this need amidst trying times. The all-hands-on-deck attitude was pervasive throughout. Researching the COVID-19 policies and piecing together the dataset one county at a time was often tedious, but everyone involved had a vision that has since become a reality and stuck with it. The fact that the project became a record-breaking crowdsourcing effort and researchers across the nation are already using it is both humbling and validating, and I’m honored to have played a part since the beginning.

This article was originally published on Harvard Business School Newsroom.

Cray Noah photo curtesy of Rachel Perry Photography.